Orientation To EpicureanFriends

Table of Contents

- 1. ORIENTATION TO EPICUREANFRIENDS.COM - The EpicureanFriends Structure

- 2. Key Concepts To Understand At the Start (The Epicurean Paradigm Shift)

- 2.1. Evidence Of Epicurus' Embrace of New Paradigms

- 2.2. The "Pleasure" Paradigm Shift

- 2.3. The "Absence of Pain" Paradigm Shift

- 2.4. The "Gods" Paradigm Shift

- 2.5. The "Virtue" Paradigm Shift

- 2.6. The "Death" Paradigm Shift

- 2.7. The "Reality" Paradigm Shift

- 2.8. The "Worlds" Paradigm Shift

- 2.9. The "Truth" Paradigm Shift

- 2.10. The "Epicurus" Paradigm Shift

- 2.11. Closing Words

- 3. Frequently Asked Questions

- 3.1. GENERAL

- 3.1.1. What Would Epicurus Say About The Search For "Meaning" in Life?

- 3.1.2. What is this debate I see in Epicurean commentary about Katastematic and Kinetic Pleasure? Ethics

- 3.1.3. How do you defend Epicurus' view of free will? Physics

- 3.1.4. What is Epicurean Philosophy All About? General

- 3.1.5. Which Is It? Is "Ataraxia" Or "Pleasure" Or "Tranquility" The Ultimate Epicurean Goal? Ethics

- 3.1.6. Are Stoics, Buddhists, Judeo-Christians, Humanists, Minimalists, et al. Welcome At EpicureanFriends? General

- 3.1.7. What Did Epicurus Mean When He Spoke of "Pleasure?"

- 3.1.8. What Are The Most Important Principles Of The Epicurean System?

- 3.1.9. What Does Epicurean Philosophy Say About "Free Will"?

- 3.1.10. Can You Suggest A Reading List For Learning About Epicurus?

- 3.1.11. What Does Epicurean Philosophy Say About Engagement With Society?

- 3.1.12. How Does Epicurean Philosophy Differ From Stoicism?

- 3.1.13. How Does Epicurean Philosophy Differ From Buddhism?

- 3.1.14. How Can I Implement Epicurean Principles As Quickly As Possible?

- 3.1.15. What Is The Epicurean Definition Of A God?

- 3.1.16. What Is The Epicurean Definition Of "Anticipations" ("Prolepsis")?

- 3.1.17. What is the Epicurean Definition of Happiness?

- 3.1.18. What Was Epicurus' Position On Skepticism and Dogmatism?

- 3.1.19. What did Epicurus say about Desire? Is All Desire Bad and To Be Minimized?

- 3.1.20. What Is The Epicurean Definition of "Virtue"?

- 3.1.21. What Did Epicurus Say About the Relationship Between Good and Evil?

- 3.1.22. What Is The Relationship Between Epicurean Philosophy And Religion?

- 3.1.23. What Would Epicurus Say To Someone Who Complains "The World Is Unjust / Life Isn't Fair"?

- 3.1.24. What Is This I Read All Over The Internet About "Katastematic" and "Kinetic" Pleasure?

- 3.2. HISTORY

- 3.3. EPISTEMOLOGY - CANONICS

- 3.4. PHYSICS - The Science of The Nature of Man and the Universe

- 3.4.1. What Did Epicurus Say About the Nature of the Universe (Physics)?

- 3.4.2. To What Extent, If Any, Does Modern Physics Invalidate Epicurean Philosophy? * How do you square modern science with Epicurean physics as to the universe having a beginning?

- 3.4.3. Was Epicurus an "Atheist?"

- 3.4.4. What did Epicurus say about whether the universe had a beginning?

- 3.4.5. What Did Epicurus Say About Whether Humans Have A "Soul"?

- 3.4.6. What did Epicurus Say about the size of the sun and whether the Earth was round or flat?

- 3.4.7. Does living happily requires a knowledge of physics, and the nature of the universe?

- 3.4.8. Does "Big Bang" Theory Invalidate Epicuran "Eternal Universe" Theory?

- 3.5. Ethics - The Science of How To Live

- 3.5.1. What Are the Central Points of Epicurean Philosophy About How To Live (Ethics)?

- 3.5.2. *What is the issue with saying that the Epicurean goal of life is Tranqulity?

- 3.5.3. What Did Epicurus Say About "The Good" and "The Greatest Good"?

- 3.5.4. What Did Epicurus Say About "The Guide" and "The Goal" of Human Life?

- 3.5.5. Does Epicurus contradict himself by seeming to say that both absence of pain and pleasure are the goal of life?

- 3.5.6. What Did Epicurus Say About Marriage?

- 3.5.7. What did Epicurus say about the value of friendship?

- 3.5.8. What Advice Did Epicurus Give About One's General Attitude Toward The Future?

- 3.5.9. Would An Epicurean Hook Himself Up To An "Experience Machine" or A "Pleasure Machine" if Possible?

- 3.6. Miscellaneous

- 3.1. GENERAL

- 4. The Major Tenets of Classical Epicurean Philosophy

- 4.1. Physics

- 4.1.1. Nothing Can Be Created From Nothing.

- 4.1.2. The Universe Is Infinite In Size And Eternal In Time And Has No Gods Over It.

- 4.1.3. The Nature of Gods Contains Nothing That Is Inconsistent With Incorruption And Blessedness

- 4.1.4. Death Is Nothing To Us.

- 4.1.5. There Is No Necessity To Live Under The Control Of Necessity.

- 4.2. Canonics

- 4.3. Ethics

- 4.4. Nothing Can Be Created From Nothing

- 4.5. The Universe Is infinite And Eternal And Has No Gods Over It

- 4.6. The Nature of Gods Contains Nothing That is Inconsistent With Blessedness And Deathlessness

- 4.7. Death Is Nothing To Us

- 4.8. There Is No Necessity To Live Under The Control of Necessity

- 4.9. He Who Says Nothing Can Be Known Knows Nothing

- 4.10. All Sensations Are True

- 4.11. Virtue Is Not Absolute Or An End In Itself; All Good And Evil Consists In Sensation

- 4.12. Pleasure Is the Guide Of Life

- 4.13. By Pleasure We Mean All Experience That Is Not Painful

- 4.14. Life Is Desirable, But Unlimited Time Contains No Greater Pleasure Than Limited Time

- 4.1. Physics

1. ORIENTATION TO EPICUREANFRIENDS.COM - The EpicureanFriends Structure

The EpicureanFriends Community is a group of people who consider themselves to be friendly to the philosophy of Epicurus, and who work together to study it themselves and promote its study by others. We are volunteers working together for a common goal, not a membership organization with elected officers or other formal structure. We applaud and support those who produce books or other materials for which they may charge a fee, but EpicureanFriends itself neither solicits nor accepts donations at this time, and we have no plans to change that in the foreseeable future.

This outline provides an introduction to the way our major projects are organized, and how we see our goal of promoting "Classical Epicurean Philosophy."

1.1. The EpicureanFriends Forum

TheEpicureanFriends forum is a place for a discussion and advocacy of Epicurean philosophy. In order to participate it is necsssary to have an account, but EpicureanFriends is not itself a membership organization with elected officers, collection of money, etc.

1.2. The EpicureanFriends Handbook

The EpicureanFriends Handbook is a static website where we are building out easier access to text and support materials,

This needs updating to include the Side-By-Side Lucretius and Diogenes Laertius, and also reference to the PDFs from TauPHi and Bryan's Usener work.

1.3. The Lucretius Today Podcast

This is our weekly podcast where we go through the Epicurean texts and discuss what they mean and how to apply them to life today.

1.4. The EpicureanFriends Youtube Page

We've produced a significant number of videos which are available here.

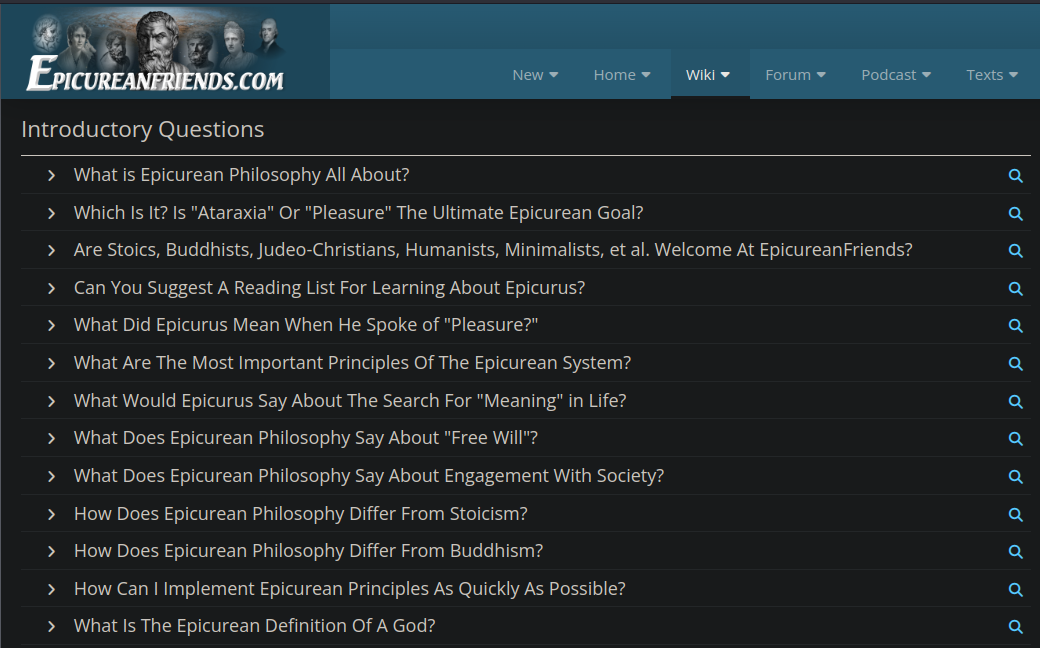

1.5. Frequently Asked Questions And Wiki

2. Key Concepts To Understand At the Start (The Epicurean Paradigm Shift)

Note: This text contains the latest revisions to this document. The original slideshow version with audio is at YouTube here, and the original text is here. Discussion of the original version is here, and discussion of the latest updated version is here. Substack version is here.

In Book Two of his work On The Ends of Good And Evil, the Roman statesman and philosopher Cicero wrote in regard to Epicurus' view of Pleasure that:

"Epicurus is speaking an idiom of his own and ignoring our accepted terminology."

As we will discuss, Cicero's complaint was ultimately unjustified, because there is nothing wrong with explaining how accepted understandings of things are in error and need to be changed. However Cicero was largely correct that Epicurus rejected important terminology that Cicero - and many people today - take for granted.

I have entitled this talk "The Epicurean Paradigm Shift" because the word "paradigm" is used today to refer to a general mental model or framework. A "Paradigm Shift" refers to a dramatic change in that mental model. In order for us to understand Epicurean philosophy correctly, we have to understand the mental model from which Epicurus developed his philosophy, and that presents certain challenges that we will discuss today.

For the next few minutes, what I am going to suggest to you is that Epicurean Philosophy should not be looked upon as a set of isolated positions, such as Atomism or Hedonism, but as a dramatic change in mental model covering a wide range of issues as to how to approach not only Pleasure but also important questions like the existence of gods and the nature of the universe and of the human soul.

To start with one quick example before diving deeper, let's start with the existence of "gods." This is one of the most confusing aspects of Epicurus for new readers, because almost everyone has been taught to consider Epicurus to be an atheist. When people first hear that Epicurus held that "gods" do in fact exist, they are immediately confused because they jump to the conclusion that they know what Epicurus meant by the word "gods." Some people close their mind to Epicurus as soon as they hear that Epicurus was considered an atheist, and other people close their mind as soon as they learn that Epicurus did not consider himself to be an atheist. If these people will stick with Epicurus long enough, however, they will find that Epicurus' views are much deeper than they imagine, because they will find that Epicurus rejected the common understanding of what it means to be a god in the first place.

That's one example of the terminology issues, but there are many more, and that explains a lot of the confusion that surrounds the study of Epicurus today. Just as in Epicurus' time, in our own day there are entrenched conventional positive and negative attitudes about gods, virtue, and pleasure, and many of those views are so strong that people think that no other views are possible.

So the first place to start in studying Epicurus is to open our minds to the possibility of a new paradigm of thought. Before we can decide whether we agree or disagree with Epicurus, we first have to first understand him clearly.

2.1. Evidence Of Epicurus' Embrace of New Paradigms

We do not have to rely on Cicero's complaints about Epicurus' terminology to see that there is in fact a real issue here. There are good reasons to conclude that the ancient Epicureans themselves knew that they were being misunderstood by some and misrepresented by others, and those reasons go right back to Epicurus himself, who wrote in his letter to Menoeceus:

"When we say, then, that pleasure is the end and aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we are understood to do by some through ignorance, prejudice, or willful misrepresentation."

- Epicurus to Menoeceus, line 131.

Vatican Saying 29 records that Epicurus also said:

In investigating nature I would prefer to speak openly and like an oracle to give answers serviceable to all mankind, even though no one should understand me, rather than to conform to popular opinions and so win the praise freely scattered by the mob.

- Epicurus, Vatican Saying 29

Likewise, in his poem on Epicurean philosophy, Lucretius warns his readers that it is necessary for them to open their minds to new possibilities. In Book Two Lucretius wrote, and here I am citing the Humphries version:

"Direct your mind

To a true system. Here is something new

For ear and eye. Nothing is ever so easy

But what, at first, is difficult to trust.

Nothing is great and marvelous, but what

All men, a little at a time, begin

To mitigate their sense of awe. Look up,

Look up at the pure bright color of the sky,

The wheeling stars, the moon, the shining sun!

If all these, all of a sudden, should arise

For the first time before our mortal sight,

What could be called more wonderful, more beyond

The heights to which aspiring mind might dare?

Nothing, I think. And yet, a sight like this,

Marvelous as it is, now draws no man

To lift his gaze to heaven's bright areas.

We are a jaded lot. But even so

Don't be too shocked by something new, too scared

To use your reasoning sense, to weigh and balance,

So that if in the end a thing seems true,

You welcome it with open arms; if false,

You do your very best to strike it down."

- Lucretius Book 2:1023 (Humphries)

Another recorded example of Epicurus's unusual phrasing is found in the work "Attic Nights" by the second-century AD Roman writer Aulus Gellius.

Plutarch, in the second book of his essay On Homer, asserts that Epicurus made use of an incomplete, perverted and faulty syllogism, and he quotes Epicurus's own words: "Death is nothing to us, for what is dissolved is without perception, and what is without perception is nothing to us." "Now Epicurus," says Plutarch, "omitted what he ought to have stated as his major premise, that death is a dissolution of body and soul, and then, to prove something else, he goes on to use the very premise that he had omitted, as if it had been stated and conceded. But this syllogism," says Plutarch, "cannot advance, unless that premise be first presented."

What Plutarch wrote as to the form and sequence of a syllogism is true enough; for if you wish to argue and reason according to the teaching of the schools, you ought to say: "Death is the dissolution of soul and body; but what is dissolved is without perception; and what is without perception is nothing to us." But we cannot suppose that Epicurus, being the man he was, omitted that part of the syllogism through ignorance, or that it was his intention to state a syllogism complete in all its members and limitations, as is done in the schools of the logicians; but since the separation of body and soul by death is self-evident, he of course did not think it necessary to call attention to what was perfectly obvious to everyone. For the same reason, too, he put the conclusion of the syllogism, not at the end, but at the beginning; for who does not see that this also was not due to inadvertence?

In Plato too you will often find syllogisms in which the order prescribed in the schools is disregarded and inverted, with a kind of lofty disdain of criticism.

In the same book, Plutarch also finds fault a second time with Epicurus for using an inappropriate word and giving it an incorrect meaning. Now Epicurus wrote as follows: "The utmost height of pleasure is the removal of everything that pains." Plutarch declares that he ought not to have said "of everything that pains," but "of everything that is painful"; for it is the removal of pain, he explains, that should be indicated, not of that which causes pain. In bringing this charge against Epicurus Plutarch is "word-chasing" with excessive minuteness and almost with frigidity; for far from hunting up such verbal meticulousness and such refinements of diction, Epicurus hunts them down.

- Aulus Gellius - Attic Nights

2.2. The "Pleasure" Paradigm Shift

Before we go further and tackle anything else, let's go back to Cicero and lock in this terminology issue as to Pleasure, since pleasure is the topic most people associate with Epicurus and are most interested in. In section 23 of Book 2 of On Ends, Cicero, who is an Academic Skeptic and very hostile to Epicurus, is speaking with Torquatus, an Epicurean. Cicero lets his exasperation and sarcasm for Epicurean philosophy come through here, so this is very revealing. Cicero says this:

The name of pleasure certainly has no dignity in it, and perhaps we do not exactly understand what is meant by it; for you are constantly saying that we do not understand what you mean by the word pleasure: no doubt it is a very difficult and obscure matter. When you speak of atoms, and spaces between worlds, things which do not exist, and which cannot possibly exist, then we understand you. Cannot we understand what pleasure is, a thing which is known to every sparrow? What will you say if I compel you to confess that I not only do know what pleasure is (for it is a pleasant emotion affecting the senses), but also that I know what you mean by the word? For at one time you mean by the word the very same thing which I have just said (which is a pleasant emotion affecting the senses), and you give it the description of consisting in motion, and of causing some variety. At another time you speak of some other highest pleasure, which is susceptible of no addition whatever, but that it is present when every sort of pain is absent, and you call it then a "state," not a "motion." Let that, then, be pleasure.

Say, in any assembly you please, that you do everything with a view to avoid suffering pain. If you do not think that this language is sufficiently dignified, or sufficiently honorable, say that you will do everything during your year of office, and during your whole life, for the sake of your own advantage; that you will do nothing except what is profitable to yourself, nothing which is not prompted by a view to your own interest. What an uproar such a declaration would excite in the assembly, and what hope do you think you would have of the consulship? Can you follow principles, which when you are alone or with your closest friends you do not dare to profess and avow openly?

But instead, you have those maxims constantly in your mouth which the Peripatetics and Stoics profess! In the courts of justice and in the senate you speak of duty, equity, dignity, good faith, uprightness, honorable actions, conduct worthy of power, worthy of the Roman people; you talk of encountering every imaginable danger in the cause of the republic — of dying for one's country. When you speak in this manner we are all amazed, like a pack of blockheads. And you are laughing in your sleeve: for, among all those high-sounding and admirable expressions, pleasure has no place, not only that pleasure which you say consists in motion, and which all men, whether living in cities or in the country, all men, in short, who speak Latin, call pleasure, but even that stationary pleasure, which no one but your sect calls pleasure at all.

- Cicero, On Ends 2:23

Here we see Cicero saying that Epicurus has a concept of pleasure "which no one but your sect calls pleasure at all."

We need to get to the bottom of that, so let's follow Cicero just a little further to see what this dispute is all about, because what we are going to find is that Epicurus held that all experiences in life - all experiences in life - fall within one of two feelings, either pleasure or pain, and Cicero refuses to accept that division.

Cicero told his Epicurean friend Torquatus that Epicurus' application of the term pleasure in this way

… does violence to one's senses; it is wresting out of our minds the understanding of words with which we are imbued. For who can avoid seeing that these three states exist in the nature of things: first, the state of being in pleasure; secondly, that of being in pain; and thirdly, that of being in such a condition as we are at this moment, and you too, I imagine, that is to say, neither in pleasure nor in pain….

- Cicero, On Ends 2:16

Here we have the crux of the issue, not only between Cicero and Torquatus, but between Epicurus and the rest of the philosophic world. Cicero is saying that there are states which do not constitute pleasure or pain, and Epicurus is saying that that is not true - that there are only pleasure and pain. Epicurus is saying that if you are alive, and feeling anything at all, you are feeling one or the other - pleasure or pain.

And what I have just said there is almost an exact quote from Torquatus. In Section 38 of On Ends Book One, Torquatus said to Cicero,

"Therefore Epicurus refused to allow that there is any middle term between pain and pleasure; what was thought by some to be a middle term, the absence of all pain, was not only itself pleasure, but the highest pleasure possible. Surely any one who is conscious of his own condition is necessarily either in a state of pleasure or in a state of pain.

- Torquatus - Cicero, On Ends 1:38

We could dedicate the rest of the time we have today to explaining that position further, but what I want to emphasis most of all is this:

Epicurus holds that death is nothing to us, which means there is no life after death, and that means that all the happiness we are ever going to experience must occur in this single life that we have. Most all of the supposed great thinkers of the world, like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics, were dedicated to some form of supernatural creation of the universe, which implies that humans are special beings with eternal souls which can continue to exist in some form after death. From Epicurus' perspective, this life is our most valuable possession and something to be enjoyed, so it makes perfect sense that we should consider every experience of life which is not painful to be pleasurable. You can decide for yourself whether you agree with Epicurus' terminology, but from this perspective it makes perfect sense to divide everything in life between that which is desirable, and call it pleasure, and that which is undesirable, and call it pain. Between those two there is no middle ground, and those who reject this division are saying more about themselves, and their own inferior view of life, than they are saying about Epicurus.

As a result of this perspective, when we look at Venus as a representation of Pleasure and Nature, as Lucretius did at the opening of his poem, we are not looking only at stimulative pleasure - the sex drugs and rock and roll of life. We are also looking at Venus as the representation of every desirable aspect of human life, mental and physical, from philosophy to sports to art to literature to music to history, from passionate love and affection to simple contemplation, and to every mental and physical activity of life in between that is not painful.

Cicero and other opponents of Epicurus strongly reject this expansion in the use of the word pleasure. In Section 7 of Book One of On Ends, Cicero tried to make an end-run around Epicurus by arguing that Epicurus never made the claim that Pleasure includes all of the mental and physical activities that I just listed. Cicero argued,

What actual pleasure do you, Torquatus, or does Triarius here, derive from literature, from history and learning, from turning the pages of the poets and committing vast quantities of verse to memory? Do not tell me that these pursuits are in themselves a pleasure to you, and that so were the deeds I mentioned of the Torquati. That line of defense was never taken by Epicurus or Metrodorus, nor by any one of them if he possessed any intelligence or had mastered the doctrines of your school.

- Cicero, On Ends 1:7

Of all the arguments made by Cicero against Epicurus, this is one of the most patently absurd. Are we to believe that there is no pleasure to be found in literature, history, poetry, and other learning? Cicero could hardly believe that Torquatus would accept this claim, and indeed Torquatus rejects it implicitly over and over again when given the chance.

No, this claim by Cicero is absurd, and there's an important lesson to be learned when an experienced trial lawyer like Cicero is willing to risk his own credibility by going over the top with an argument that no one with any knowledge of Epicurus would believe. What Cicero is doing is making an argument that is patently false, and instead of accepting Epicurus' view of pleasure and disagreeing on the merits, Cicero tries to ridicule Epicurus, throughout his book, by calling Epicurus's position effeminate and cowardly and disreputable. Rather than dealing honestly with ideas, Cicero is deflecting our attention and asking us to consider whether any normal, proud, strong, and vigorous man or woman would possibly accept "absence of pain" as the goal of their lives.

The answer to that, is of course they would not, given Cicero's definition of pleasure as limited to sensual stimulation. But that's not the definition of pleasure that Epicurus stated, or the Epicureans were working with. And that's something that Cicero, and people who think like Cicero, refuse to acknowledge.

This is an important question that demands a response, but Cicero controlled the terms of the debate in On Ends, and he never gave Torquatus the opportunity to address it in detail. Cicero was counting on the fact that - just like today - many people do in fact jump to the conclusion that "pleasure" means "sensual stimulation" only, because they have not heard the full Epicurean explanation of Pleasure. Just as Epicurus complained to Menoeceus, it is very easy for Epicurus' enemies to deceive and say that when Epicurus speaks of pleasure all he means is bodily stimulation.

Why would Cicero take such a risk in making an argument that can be easily refuted, and which the information in Cicero's own book refutes? Because Epicurus's enemies, from the Stoics, to Cicero, to Plutarch, and on to the Jews and the Christians who came afterward, totally reject Epicurus's view that there are no supernatural gods. Epicurus's enemies promote piety to the gods or Virtue or Reason as the organizing principles of life, and they know that what Epicurus taught meant the total rejection of their own principles of life.

In educating people to what Pleasure really means, and showing them how a life of pleasure can in fact be achieved, Epicurus was leading a philosophical and moral revolution. Cicero rightly saw that the continued spread of Epicurean philosophy would have spelled the end of supernatural-based ethis in the educated world.

Norman DeWitt, the Canadian Professor who authored the book Epicurus And His Philosophy, expressed what Epicurus was doing in this way:

“The extension of the name of pleasure to the normal state of being was the major innovation of the new hedonism. It was in the negative form, freedom from pain of body and distress of mind, that it drew the most persistent and vigorous condemnation from adversaries. The contention was that the application of the name of pleasure to this state was unjustified on the ground that two different things were thereby being denominated by one name. Cicero made a great to-do over this argument, but it is really superficial and captious. The fact that the name of pleasure was not customarily applied to the normal or static state did not alter the fact that the name ought to be applied to it; nor that reason justified the application; nor that human beings would be the happier for so reasoning and believing."

- Norman DeWitt - Epicurus and His Philosophy, p. 240

2.3. The "Absence of Pain" Paradigm Shift

Before we move on, let's say a little more about the paradigm shift involved in "absence of pain."

Today, this term is often misinterpreted as Epicurus abandoning the normal active and stimulating mental and bodily pleasures in favor of a Buddhist-like or Stoic-like indifference, or aloofness, or asceticism. This could not be further from the truth. As we have already discussed, Epicurus held that there are only two feelings - pleasure and pain. When there are only two options of anything, then the absence of one equals the presence of the other.

One way to think of this is as a Pie chart divided by a line into two parts, with one side representing pleasure and the other representing pain. No matter how you draw the dividing line, everything on one side of the line is pleasure, and the other is pain. The part of the chart that is not pain - where pain is absent - is therefore pleasure, and vice versa. In this paradigm, the term "absence of pain" means nothing more, or less, than "Pleasure."

In this way we see what Cicero refused to admit: that the term "absence of pain" does not indicate a special or higher type of pleasure, but pleasure itself, in any of the many active or stable forms in which it can exist. Dividing all of experience into the two categories of pleasure and pain in this way does not tell us what type of pleasure or pain is involved in a particular life at a particular moment, but it does tell us that in general, we want as much of our experience to be pleasurable, and as little of our experience to be painful, as possible.

Epicurus' enemies, and even many who profess to be his friend but who are or more of Stoic or Ascetic bent, have turned this perspective on its head, and ended up making it look like the primary goal of Epicurean philosophy is to run like a coward from every moment of pain no matter how slight. Again, nothing could be further from the truth. Epicurus clearly tells us that we will regularly choose activities that are painful, when those activities increase our total pleasure, and that in fact the cowardly and shameful person is he who always chooses pleasure even when he or she should see that that choice will lead ultimately to disaster.

Nothing could be more clear than Torquatus' explanation of this:

… [[W]e denounce with righteous indignation and dislike men who are so beguiled and demoralized by the charms of the pleasure of the moment, so blinded by desire, that they cannot foresee the pain and trouble that are bound to ensue; and equal blame belongs to those who fail in their duty through weakness of will, which is the same as saying through shrinking from toil and pain. These cases are perfectly simple and easy to distinguish. In a free hour, when our power of choice is untrammelled and when nothing prevents our being able to do what we like best, every pleasure is to be welcomed and every pain avoided.

But in certain emergencies and owing to the claims of duty or the obligations of business it will frequently occur that pleasures have to be repudiated and annoyances accepted. The wise man therefore always holds in these matters to this principle of selection: he rejects pleasures to secure other greater pleasures, or else he endures pains to avoid worse pain.

- Torquatus - Cicero's On Ends Book 1:10

By now in my talk it is clear that even though Cicero was a strong critic of Epicurus, we have much to thank Cicero for, because Cicero preserved for much detail about Epicurean arguments that would otherwise be lost. And those who read the letter to Menoeceus over and over again without the illustrations that Torquatus provides are doing themselves a major disservice.

Possibly the most important illustration that Cicero preserved through Torquatus is a story about an argument made against Epicurus by the famous Stoic philosopher Chrysippus.

The argument strikes many of us as strange the first time we hear it, but if you'll stay with me I think you'll see something very important. Here's the story Torquatus told in Section 11 of Book One of On Ends, and it involves Chrysippus holding out his hand, and making a short logical argument to an unknown person who apparently does not understand Epicurus.

Here's the story:

"At Athens, so my father used to tell me when he wanted to air his wit at the expense of the Stoics, in the Ceramicus there is a statue of Chrysippus seated and holding out one hand, the gesture being intended to indicate the delight which Chrysippus used to take in the following little syllogism:

“Does your hand want anything, while it is in its present condition?”

“No, nothing.”

“But if pleasure were a good, it would want pleasure.”

“Yes, I suppose it would.”

“Therefore pleasure is not a good.”

This is an argument, my father declared, which not even a statue would employ, if a statue could speak; because though it is cogent enough as an objection to the Cyrenaics, it does not touch Epicurus. For if the only kind of pleasure were that which so to speak tickles the senses, an influence permeating them with a feeling of delight, neither the hand, nor any other part of the body, could be satisfied with the absence of pain unaccompanied by an agreeable and active sensation of pleasure.

Whereas if, as Epicurus holds, the highest pleasure be to feel no pain, Chrysippus's interlocutor, though justified in making his first admission (that his hand in that condition wanted nothing) was not justified in his second admission (that if pleasure were a good, his hand would have wanted it).

And the reason why it would not have wanted pleasure is that to be without pain is to be in a state of pleasure.

- Torquatus - Cicero's On Ends 1:11

What does this mean? Again, this can be confusing, as the Stoics like to be. We don't normally think about our hands in their normal condition wanting or lacking pleasure or anything else. But thinking about that is the key to understanding the analogy and why Chrysippus's point is false. Chrysippus was presuming that we would agree with him, and in fact we do, that if a thing is the highest good for a living thing, then any living thing that lacks that thing will want it, and be dissatisfied, or even in pain, from the lack of it.

Just like Cicero is doing, Chryssipus is trying to get us to accept that the only type of pleasure is sensual stimulation, and in fact Torquatus points out for us that that is exactly what Aristippus, and the Cyreniacs, did in fact believe. In other words if the only kind of pleasure that exists for our hand is that of being massaged, or being immersed in a warm bath, then if the goal of life is pleasure then our hands would be satisfied unless they were constantly being massaged or warmed. Cicero and the Stoics are both saying that if Pleasure is the goal of life, and Pleasure consists only in stimulation, no living being, whether a hand or a full person, could ever be satisfied, and thus it would be in pain, unless it had sensual stimulation.

And of course the enemies of Epicurus also want you to focus on the fact - with which Epicurus agrees - that sensual stimulation is not something you can expect to be constant and uninterrupted for your whole life. So therefore they want you to conclude that considering Pleasure to be the goal of life and the highest good is not only disreputable but a fool's errand that is doomed to failure.

The Epicurean response to this is very clear, and Torquatus gives it:

Under Epicurus' sweeping view of pleasure, the defoault position of simply being alive in a healthy state is pleasurable. Whether we are talking about our hand or any other living thing, if we are not experiencing pain and we are in a normal and healthy state then what we are experiencing is pleasure. And even when we may be experiencing physical pain, Torquatus makes clear that physical pain can be outweighed by mental pleasure. Torquatus says this:

This therefore clearly appears, that intense mental pleasure or distress contributes more to our happiness or misery than a bodily pleasure or pain of equal duration. But we do not agree that when pleasure is withdrawn uneasiness at once ensues, unless the pleasure happens to have been replaced by a pain: while on the other hand one is glad to lose a pain even though no active sensation of pleasure comes in its place: and this fact serves to show how great a pleasure is the mere absence of pain.

- Torquatus - Cicero, On Ends Book 1:18

As we will mention later, the story of Epicurus being happy even while in great physical pain on the last day of his life makes this same point. So far is Epicurus from valuing only bodily pleasures, that he emphasized using his own example that mental pleasures are frequently of much greater importance to us than are bodily ones.

This view of pleasure does in fact reject the terminology that Cicero and the rest of the philosophers insist on using. However as Norman Dewitt said, this change in paradigm is fully justified, and humanity would be far better off by recognizing and reasoning that Epicurus's approach to pleasure is correct.

And what could be more true than to observe that when the total experience of the hand, or a person as a whole, is without any pain, than that the total experience is the highest amount of pleasure possible? Such an experience is pure pleasure with no mixture of pain, and fully justifies the label of "the highest pleasure," even if we are not specifying whether the person is sitting calmly at rest or rocketing himself to Mars to experience the exhilaration of exploration. Both of these examples, or any example in which it is stated that no pain is present, are rightly considered to be "the highest pleasure." Cicero in fact provides later in the same work just such an example, which left Cicero astounded, that the Epicureans could consider both the host at a banquet who is without pain but pouring wine for a guest, as experiencing the same amount of pleasure as the thirsty guest who is relieving his thirst and is also otherwise without pain.

The point of that story as well, is that if it is stated that you are without pain, then you are without pain, and at the theoretical peak of pleasure.

We frequently hear the objection "How can absence of pain be the "peak" of Pleasure?" Here we can look back to both the words and the life of Epicurus for guidance on how much pleasure a person should seek.

In his letter to Menoeceus, Epicurus tells us repeatedly that the goal of life is pleasure, and that we should the most pleasant life, but Epicurus does notseek to substitute his judgment for ours as to what each person will be find to be most pleasant life for them.

Just as with food the wise man does not seek simply the larger share and nothing else, but rather the most pleasant, so he seeks to enjoy to the longest period of time, but the most pleasant.

…

Independence of desire we think a great good — not that we may at all times enjoy but a few things, but that, if we do not possess many, we may enjoy the few in the genuine persuasion that those have the sweetest pleasure in luxury who least need it. …

- Epicurus, Letter to Menoeceus

Epicurus tells Menoeceus that "every pleasure because of its natural kinship to us is good," but that some pleasures are not to be chosen because in the end they do bring more pain than pleasure. Epicurus tells everyone in Principal Doctrine 10 that:

If the things that produce the pleasures of profligates could dispel the fears of the mind about the phenomena of the sky, and death, and its pains, and also teach the limits of desires and of pains, we should never have cause to blame them: for they would be filling themselves full, with pleasures from every source, and never have pain of body or mind, which is the evil of life.

- Epicurus, Principal Doctrine 10

All of those point in the same direction, that Epicurus is not going to tell us what is the most pleasurable life for us. He's going to let Nature tell us that, directly, given the circumstances of our own lives. Epicurus is a philosopher, not a life coach, and as you would expect from a philosopher who rejects the idea of a central supernatural plan for the universe as a whole, Epicurus generally writes in broad philosophic terms that are appropriate for someone who realizes that our specific personal circumstances will generally control what we find to be most pleasant and most painful for us. Epicurus always tracks his underlying premises about the nature of the universe, and therefore when each of us reaches the end of our lives, whenever that may be, it is only we ourselves - and no supernatural god or anyone else - whose opinion counts as to whether we have made the best use of our lives.

In Epicurus' own case, we have the biography of Diogenes Laertius as evidence that Epicurus was far from choosing a life of minimalism or asceticism for himself. Few men who choose a life of asceticism have any need to write a will disposing of extensive personal property, but Epicurus' will shows us that at the time of his death Epicurus held not only the "garden" that is associated with his name, Epicurus held also a house in Milete, which appears to have generated income sufficient for a number of purposes, including caring for the son of Metrodorus, for the son of Polyaenus, and for the daughter of Metrodorus. Epicurus also appears to have held at least four slaves, whom he freed at his death, and possibly a larger number that he did not. To the example of Epicurus we can also point to Diogenes of Oinoanda, who was well off enough at the end of his life to endow a large public monument dedicated to Epicurus. We can also look to other Epicureans such as Cicero's friend Atticus or Philodemus' patron Piso, all of whom were very wealthy. These are not the markings of men who believed that Epicurean philosophy pointed them toward any form of asceticism or minimalism.

Epicurus regularly challenges us to think outside the box by using phrases such as "death is nothing to us," or "the size of the sun is as it appears to be." The use of terminology that equates Pleasure with "Absence of Pain" is not only challenging but it is also maddening to those people like Cicero who refuse to accept any other way of thinking than their own. But in the end, stating proudly that the goal of life is "Absence of Pain" is just as aggressive - just as confrontational - and just as correct - as stating that the goal of life is Pleasure.

Cicero tried to argue Torquatus down from this position, but Torquatus stood his ground without hesitation.

At Section 9 of Book 2 of On Ends, Cicero argued:

“…[B]ut unless you are extraordinarily obstinate you are bound to admit that 'freedom from pain' does not mean the same thing as 'pleasure.'”

Torquatus replied:

“Well but on this point you will find me obstinate, for the fact that freedom from pain means pleasure is as true as any proposition can be.”

- Cicero On Ends 2:9

Some who resist Epicurus' view of pleasure will say that he is playing a word game, and that on most occasions our immediate experience is a combination of pleasures and pains. But Epicurus himself provides the example that in proves the rule of what he was asserting.

As Diogenes Laertius records:

When he was on the point of death Epicurus wrote the following letter to Idomeneus: ‘On this truly happy day of my life, as I am at the point of death, I write this to you. The disease in my bladder and stomach are pursuing their course, lacking nothing of their natural severity: but against all this is the joy in my heart at the recollection of my conversations with you. Do, as I might expect from your devotion from boyhood to me and to philosophy, take good care of the children of Metrodorus.

- Diogenes Laertius 10:22

So on the last day of his life, Epicurus was experiencing both severe bodily pain and mental pleasure at the thought of his philosophical achievements and the company of his friends. Nevertheless, Epicurus wrote that this last day of his life was also among his happiest.

Epicurus knew that because we are humans must expect a combination of pleasures and pains. As Torquatus explains for us Epicurean philosophy gives us the key to understanding that it is within our power to live a life in which pleasure predominates.

As Torquatus explained in Section 62 of Book One of On Ends:

For this is the way in which Epicurus represents the wise man as continually happy; he keeps his passions within bounds; about death he is indifferent; he holds true views concerning the eternal gods apart from all dread; he has no hesitation in crossing the boundary of life, if that be the better course. Furnished with these advantages he is continually in a state of pleasure, and there is in truth no moment at which he does not experience more pleasures than pains. For he remembers the past with thankfulness, and the present is so much his own that he is aware of its importance and its agreeableness, nor is he in dependence on the future, but awaits it while enjoying the present; he is also very far removed from those defects of character which I quoted a little time ago, and when he compares the fool’s life with his own, he feels great pleasure. And pains, if any befall him, have never power enough to prevent the wise man from finding more reasons for joy than for vexation.

- Torquatus - Cicero, On Ends 1:62

If this analysis of "Absence of Pain" is correct, it would be nice to find some ancient authority making the same point outside of Cicero's work. We can cite at least one instance of this in the previously-mentioned work of Aulus Gellius. In addition to defending Epicurus' non-standard use of logical phrasing as to death, Gellius provides us no less an example than Homer himself as someone who emphasized the height of something by referring to it as the extreme point of its opposite. Here is the text, again from "Attic Nights," where Gellius gives examples of this device and says that Epicurus was using it himself as to "absence of pain."

There is absolutely no one who is of so perverted a character as not sometimes to do or say something that can be commended (laudari). And therefore this very ancient line has become a familiar proverb:

Oft-times even a fool expresses himself to the purpose.

But one who, on the contrary, in his every act and at all times, deserves no praise (laude) at all is inlaudatus, and such a man is the very worst and most despicable of all mortals, just as "freedom from all reproach" makes one inculpatus (blameless).

Now inculpatus is the synonym for perfect goodness; therefore conversely inlaudatus represents the limit of extreme wickedness. It is for that reason that Homer usually bestows high praise, not by enumerating virtues, but by denying faults; for example:

“And not unwillingly they charged,”

and again:

“Not then would you divine Atrides see Confused, inactive, nor yet loath to fight.”

Epicurus too in a similar way defined the greatest pleasure as the removal and absence of all pain, in these words: “The utmost height of pleasure is the removal of all that pains.”

Again Virgil on the same principle called the Stygian pool “unlovely.” For just as he expressed abhorrence of the “unpraised” man by the denial of praise, so he abhorred the “unlovable” by the denial of love.

So in this example we can see that we need not consider "absence of pain" to be a new paradigm at all. If Homer can "usually bestow high praise, not by enumerating virtues, but by denying faults, then Epicurus is perfectly within his rights to use "absence of pain" as the "height of pleasure." Using Gellius' phrasing and applying it to pleasure and pain, we can begin to make this phrasing more familiar to us be seeing that just as "absence of pain" is the synonym for perfect pleasure, therefore conversely "absence of pleasure" represents the limit of extreme pain.

For those who have not thought about this wording beforehand, it might not be advisable to surprise your romantic partner by telling him or her that they represent "absence of pain" to you. But figuring problems like this out is exactly what Epicurean philosophy requires of us, and indeed Epicurus is noted by Norman DeWitt to have said just that:

To substantiate this drift of reasoning it is not impossible to quote a text:

The stable condition of well-being in the flesh and the confident hope of its continuance means the most exquisite and infallible of joys for those who are capable of figuring the problem out.

DeWitt page 233, citing Usener 68.

2.4. The "Gods" Paradigm Shift

At this point I have used up most of my time, but let me quickly mention several more paradigm shifts, turning next to the second most important of them all.

As we've already mentioned, people today or conditioned to think that you either believe in a supernatural god or you are an atheist. Almost everyone today thinks of gods as omnipotent and omniscient and omnipresent – all sorts of "omni" supernatural characteristics – and they think if you reject those characteristics you're rejecting the very possibility of there being a god of any kind.

The truth is that Epicurus held neither of those positions. Epicurus held that divine beings do exist, but that divine beings are an absolutely natural part of our universe, just like everything else, and certainly not supernatural. Epicurus wrote to Menoeceus:

For gods there are, since the knowledge of them is by clear vision. But they are not such as the many believe them to be: for indeed they do not consistently represent them as they believe them to be. And the impious man is not he who popularly denies the gods of the many, but he who attaches to the gods the beliefs of the many.

- Epicurus's Letter to Menoeceus

Epicurus held that to be a god means to be totally happy, and totally without worry of anything, including death. Epicurean gods may be at the top of "successful living" pyramid, but Epicurean gods are in no way supernatural. Epicurean gods do not create universes or in any way meddle in the affairs of human beings, any more than we generally take it upon ourselves to go looking to cause trouble for ants.

Because gods are totally natural and take no notice of us, we as humans have absolutely no reason to fear them. And to the extent that the subject of gods should cross our minds at all, it should be as a part of our understanding that the universe contains infinite amounts of life, and that it is helpful to us to consider how a totally happy being who is totally unconcerned about death might live. Epicurus famously stated that it is possible through the study of philosophy to live like a "god among men," and Lucretius repeated the analogy in comparing the blessedness of Epicurus' life to that of a god.

This view of divinity is not atheism as we use that word today, but it totally eliminates the need to be concerned about controlling or angry or loving gods as suggested by many religions and philosophies. And more than that, it helps us focus on the fact that just as with any gods that exist, we too are a part of Nature and not the focus of attention of some arbitrary supernatural god.

2.5. The "Virtue" Paradigm Shift

Turning quickly to Virtue,in contrast to the Stoics Epicurus denied that virtue is an end in itself, or the same for all people at all times and at all places. Epicurus held the general term for the true goal of life is Pleasure, and that virtue is a tool - inseparable and necessary - that we need for living pleasurably.

Most people in Epicurus's age and even today angrily reject this viewpoint, but it is the logical conclusion of identifying that there can be only one "greatest" good in life. Remember, Epicurus is a philosopher, and what he is trying to do is to give you a framework through which you can think your way out of the box that the other philosophers and religions want to keep you inside.

This issue became such a major question with the rise of Stoicism that the Epicurean Diogenes of Oinoanda had to resort to "shouting" about it on the wall that he erected to celebrate the benefits of Epicurean philosophy. Diogenes wrote about those who have views similar to Stoicism on his wall in what we now have as Fragment 32:

If, gentlemen, the point at issue between these people and us involved inquiry into "what is the means of happiness?" and they wanted to say "the virtues" (which would actually be true), it would be unnecessary to take any other step than to agree with them about this, without more ado. But since, as I say, the issue is not "what is the means of happiness?" but "what is happiness and what is the ultimate goal of our nature?," I say both now and always, shouting out loudly to all Greeks and non-Greeks alike, that pleasure is the end of the best mode of life, while the virtues, which are inopportunely messed about by these people (being transferred from the place of the means to that of the end), are in no way an end, but the means to the end.

- Inscription of Diogenes of Oinoanda, fragment 32

2.6. The "Death" Paradigm Shift

Turning next to Epicurus' famous statement, "Death Is Nothing To Us" - this is a statement that derives from Epicurus' conclusion in the field of Physics that human consciousness ceases to exist when the body dies. Because we no longer exist, it is impossible for us to receive after death any reward or punishment for anything that we do in this life, or to have any consciousness whatsoever.

Epicurus wrote to Menoeceus:

Become accustomed to the belief that death is nothing to us. For all good and evil consists in sensation, but death is deprivation of sensation. And therefore a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not because it adds to it an infinite span of time, but because it takes away the craving for immortality. For there is nothing terrible in life for the man who has truly comprehended that there is nothing terrible in not living.

- Epicurus' Letter to Menoeceus

This doesn't mean of course that we should not be concerned about the welfare of our friends after we die, or the time and manner of our own death. Epicurus taught that life is desirable, and a painful death is certainly undesirable. When we realize that our time is limited, that helps us to relish the time that we do have, and it even motivates us to provide for the future of our friends who will live after us, just as Epicurus himself left a will and provided for his school and for the daughter of Metrodorus after his own death.

Epicurus didn't cavalierly refuse to think about death, and neither should we. Epicurus taught that what is important is to realize that after we die we no longer exist forever, and that is a state of nothingness in which we will have no pain or pleasure of any kind. For that reason the old expression applies about making use of your time, "make hay while the sun shines."

2.7. The "Reality" Paradigm Shift

Another poorly-understood phrase often associated with Epicurean philosophy is that "nothing exists except atoms and void." This a view that originated with Democritus rather than Epicurus, and Epicurus was emphatic in separating himself from the conclusions that some draw from it. To say that all things are composed of atoms and void does not mean that the things we see around us are not real, and it does not lead to skepticism or nihilism, as it seems to have done, at least to some extent, for Democritus himself. Epicurus was emphatic in pointing out the mistakes of Democritus' conclusions.

Professor David Sedley, one of the great experts on Epicurus today, explains the point this way in his article entitled "Epicurus' Refutation of Determinism:"

"Because phenomenal objects and properties [the things we see around us] seemed to reduce to mere configurations of atoms and void, Democritus was inclined to suppose that the atoms and void were real while the phenomenal objects and properties were no more than arbitrary constructions placed upon them by human cognitive organs. In his more extreme moods, Democritus was even inclined to doubt the power of human judgment, since judgment itself was no more than a realignment of atoms in the mind.

Epicurus' response to this is perhaps the least appreciated aspect of his thought. It was to reject reductionist atomism. Almost uniquely among Greek philosophers, [Epicurus] arrived at what is nowadays the unreflective assumption of almost anyone with a smattering of science, that there are truths at the microscopic level of elementary particles, and further very different truths at the phenomenal level; that the former must be capable of explaining the latter; but that neither level of description has a monopoly of truth. The truth that sugar is sweet is not straightforwardly reducible to the truth that it has such and such a molecular structure, even though the latter truth may be required in order to explain the former. By establishing that cognitive skepticism, the direct outcome of reductionist atomism, is self-refuting and untenable in practice, Epicurus justifies his non-reductionist alternative, according to which sensations are true and there are therefore bona fide truths at the phenomenal level accessible through them.

-David Sedley, "Epicurus' Refutation of Determinism"

In other words, while nothing has an eternal and unchanging nature except the atoms and the void and the universe a whole, we ourselves - and the things we see around us - everything we love, from our dogs, to our cats, to our houses, to everything around us that we see and touch every day - those things are real too. It's very damaging to think that these things are somehow less real than the atoms and the void, because what that often leads to is the idea that only the atoms and void are real, and that everything else is a figment of our imagination, and that leads to nihilism and helplessness which is the furthest thing from Epicurean Philosophy possible.

Now we are accelerating towards our close with just a few more comments:

2.8. The "Worlds" Paradigm Shift

For Epicurus the term "World" refers not just to the Earth, but to all that we see in the sky as well, including the sun, the moon, the stars, and the planets. And in an infinite universe, there are infinite number of worlds. Lucretius says it this way in Book Two of his poem.

If there is so great a store of seeds as the whole life of living things could not number, and if the same force and nature abides which could throw together the seeds of things, each into their place in like manner as they are thrown together here, you must confess that there are other worlds in other regions, and diverse races of men and tribes of wild beasts. In the universe there is nothing single, nothing born unique and growing unique and alone, but it is always of some tribe, and there are many things in the same race. First of all turn your mind to living creatures; you will find that in this direction is begotten the race of wild beasts that haunts the mountains, in this direction the stock of men, in this direction again the dumb herds of scaly fishes, and all the bodies of flying fowls. Wherefore you must confess in the same way that sky and earth and sun, moon, sea, and all else that exists, are not unique, but rather numberless; inasmuch as the deep-fixed boundary-stone of life awaits these as surely, and they are just as much of a body that has birth, as every race which is here on earth, abounding in things after its kind.

- Lucretius, Book 2:1067

So when you read the word "World," Epicurus tells us that there are an infinite number of worlds, other collections of planets and stars and galaxies and living beings.

Epicurus held that because Nature never creates only a single thing of a kind, we expect there to be innumerable worlds in the universe where life both similar and different from ours exists.

So that here on Earth as humans, we are not by any means the only, or the most intelligent, life that exists in the universe, nor are we the center of the universe, or the center of attention of a god that chooses certain peoples to be his friends and others to be his enemies.

Views such as that are totally irreconcilable with Epicurean philosophy.

2.9. The "Truth" Paradigm Shift

Also - when you read Epicurus you'll often see references to a "Canon of Truth," and you need to understand that this does not refer to a book of propositions like a rulebook or a Bible, but to a "test" of truth, similar to a ruler or a yardstick by which we measure distance. A ruler can be applied to any object to measure its size, but it tells us nothing more about that object other than how it compares to a known quantity. For example, a ruler tells us that both a human foot and a football are approximately a foot long, but the ruler does not tell us the nature of a human foot or a football or that they are very different things.

Epicurus' biographer Diogenes Laertius explains the Canon of Truth this way:

Logic they reject as misleading. For they say it is sufficient for physicists to be guided by what things say of themselves. Thus in The Canon Epicurus says that the tests of truth are the sensations and the preconceptions and the feelings…. For, he says, all sensation is irrational and does not admit of memory; for it is not set in motion by itself, nor when it is set in motion by something else, can it add to or take from it.

Diogenes Laertius Book 10:31

For Epicurus the ultimate test of reality is not syllogisms or abstract logic, but whether a thing can be felt or measured when tested by the faculties given us by nature, including the five senses, the intuitive faculty known as "preconception," or the feeling of pleasure and pain.

Because these faculties are given to us by Nature, it is they to which we look to validate all our reasoning, and so from that perspective "all sensations are true." These natural faculties have no memory or reasoning of their own, and they never lie to us, so everything that they report to us has to be accounted for if we want to fill in the picture of whatever they are reporting to us.

Error can certainly take place in our reasoning about what the senses report to us, but the senses themselves never lie - they simply report what they receive without any added opinion of their own, and it is up to us in our mind to process that result.

2.10. The "Epicurus" Paradigm Shift

I only have time for one more paradigm shift before we close, but I'd like to suggest that this can be the most important. In the end, the most life-changing paradigm shift that can come from the study of Epicurus is to see that Epicurus is not the philosopher of shy retiring ascetic wallflowers who avoid engagement with the world and who seek only quiet, simplicity, minimalism, and even austerity, as some people would have you to believe.

Once you understand the Epicurean view of life, you will see that Epicurus is the philosopher of people who are healthy, active, and vigorously alive, and who understand that life is short, and that we should work as hard as we can to make the best of the time that we have while we are alive.

As stated in Vatican Saying 47, an Epicurean will seize the day and approach life aggressively:

I have anticipated thee, Fortune, and entrenched myself against all thy secret attacks. And I will not give myself up as captive to thee or to any other circumstance; but when it is time for me to go, spitting contempt on life and on those who vainly cling to it, I will leave life crying aloud a glorious triumph-song that I have lived well.

- Epicurus, Vatican Saying 47

In the ancient world Epicurus appealed to large numbers of people, but the followers of Epicurus who you are almost never told about include Roman generals such as Cassius Longinus, Gaius Panza, and other leaders of Julius Caesar's camp, quite possibly including Julius Caesar himself, who at the very least held a number of very Epicurean ideas. These men led full and active lives, vigorously engaged with the world around them.

Once again we can thank Cicero for the preservation of an important Epicurean text. In 45 BC, in the middle of the Roman Civil War, Cassius Longinus tried to explain Epicurean philosophy to Cicero. We have Cassius's letter in which he wrote to Cicero the following:

"It is hard to convince men that "the good is to be chosen for its own sake;" but that pleasure and tranquility of mind is acquired by virtue, justice, and the good is both true and demonstrable. Why, Epicurus himself, from whom all the Catiuses and Amafiniuses in the world, incompetent translators of terms as they are, derive their origin, lays it down that "to live a life of pleasure is impossible without living a life of virtue and justice." Consequently Pansa, who follows pleasure, keeps his hold on virtue, and those also whom you call pleasure-lovers are lovers of what is good and lovers of justice, and cultivate and keep all the virtues."

- Cassius To Cicero, January, 45 BC

We'll never know whether Cicero truly had a change of heart about Epicurean philosophy at the very end of his life, but we do know that Cicero admitted to Cassius that Cassius' actions had made him reevaluate his attitude toward Epicurus.

Near the end of his life Cicero wrote this to Cassius:

" …[T]o whom am I talking? To you, the most gallant gentleman in the world, who, ever since you set foot in the forum, have done nothing but what bears every mark of the most impressive distinction. Why, in that very school you have selected I apprehend that there is more vitality than I should have supposed, if only because it has your approval."

- Cicero To Cassius, January, 45 BC

For those of us who are alive today, we have the chance that Cicero missed to look further into Epicurean philosophy and see how it can shift our own understanding of the universe and our place in it.

The next step in the study of Epicurus is up to you. As Lucretius said at Book one line 398 of his poem to the student of Epicurean philosophy:

"For as dogs often discover by smell the lair of a mountain-ranging wild beast, though covered over with leaves, when once they have got on the sure track, thus you in cases like this will be able by yourself alone to see one thing after another and find your way into all dark corners and draw forth the truth."

- Lucretius 1:398 (Munro)

2.11. Closing Words

As we close now, if there is anything that I would impress on your mind about what we have discussed, it is this:

Don't presume that Epicurus is speaking to you the way everyone else does. Read back into the original texts, not only from Diogenes Laertius and Diogenes of Oinoanda and Lucretius, but also from Cicero's On Ends and other reputable authorities. Sometimes even Epicurus' enemies understand him better than do some of his self-styled friends.

To help you get there the fastest and with the broadest perspective, I recommend Norman DeWitt's Epicurus and His Philosophy. If you are not already familiar with Greek philosophy, you will probably want to start with DeWitt before you read anything else.

Above all, don't let the Greek words or the non-standard terminology intimidate you. As Epicurus himself suggested, put everything into an outline so you can see the big and consistent picture and how it impacts the separate doctrines, especially the most important ones about gods, and death, and pleasure.

Don't look for mystical meaning behind phrasing you don't understand - above all as to "absence of pain." In the end, as Cicero also said, Epicurean philosophy is simple and straightforward. There are no supernatural gods. There is no life after death. There are no absolute virtues to which you have to conform. From this perspective, everything in life should be viewed as either pleasure or pain, and "absence of pain" means nothing more than "pleasure." Yes, the complete absence of all pain is by definition the highest pleasure, and when you're debating with other philosophers who tell you that pleasure can't be the best there is because there is no limit to the search for pleasure, that can be your answer to them. Principal Doctrine 3: The limit of quantity in pleasures is the removal of all that is painful. Wherever pleasure is present, as long as it is there, there is neither pain of body, nor of mind, nor of both at once.

And you do need to remember that, because depending on the people you spend your time with, there will be Ciceros and Senecas and Stoics and Platonists and Aristotelians and others who will constantly try to talk you down from having confidence in your position.

But what most of you really want to know is something else: How should you spend your time? What pleasures should you pursue? What pains should you avoid? And there it's up to you to weigh the options that are available to you. No one has authority from god or anywhere else to make those decisions for you. Consider all the options as intelligently as you can, and think about such things as intensity, duration, and parts of your mind or body that will be involved. Then, make the choice that you think you'll be happiest with when you get to the end of your life and look back at how you spent it. After you die there will be no gods or magic Epicureans to tell you "well done," but if you remember that Pleasure means everything in life - mental, emotional, physical - everything in life that you find to be desirable - then you will have taken to heart Epicurus's advice when he said "And just as with food he does not seek simply the larger share and nothing else, but rather the most pleasant, so he seeks to enjoy not the longest period of time, but the most pleasant."

Thank you for your time.

3. Frequently Asked Questions

3.1. GENERAL

3.1.1. What Would Epicurus Say About The Search For "Meaning" in Life?

The starting point for answering this question is much the same as asking about any other decision about what to pursue. The place to start is to identify the ultimate goal or thing to pursue in life, and decide whether "meaning" or "meaningfulness" is some part or all of that goal. Epicurus holds that the highest good in life is Pleasure, which is the first and natural good.

Letter to Menoeceus [129]: And for this cause we call pleasure the beginning and end of the blessed life. For we recognize pleasure as the first good innate in us, and from pleasure we begin every act of choice and avoidance, and to pleasure we return again, using the feeling as the standard by which we judge every good.

Authoritative texts hammer home the point that the highest good in life is "Pleasure."

Cicero: On Ends Book One - [29] IX. “‘First, then,’ said he, ‘I shall plead my case on the lines laid down by the founder of our school himself: I shall define the essence and features of the problem before us, not because I imagine you to be unacquainted with them, but with a view to the methodical progress of my speech. The problem before us then is, what is the climax and standard of things good, and this in the opinion of all philosophers must needs be such that we are bound to test all things by it, but the standard itself by nothing. Epicurus places this standard in pleasure, which he lays down to be the supreme good, while pain is the supreme evil….”

Cicero: On Ends Book One “Nor indeed can our mind find any other ground whereon to take its stand as though already at the goal; and all its fears and sorrows are comprised under the term pain, nor is there any other thing besides which is able merely by its own character to cause us vexation or pangs In addition to this the germs of desire and aversion and generally of action originate either in pleasure or in pain.” [42] This being so, it is plain that all right and praiseworthy action has the life of pleasure for its aim. Now inasmuch as the climax or goal or limit of things good (which the Greeks term telos) is that object which is not a means to the attainment of any thing else, while all other things are a means to its attainment, we must allow that the climax of things good is to live pleasurably.“

Diogenes of Oinoanda, Fragment 32: “I shall discuss folly shortly, the virtues and pleasure now. If, gentlemen, the point at issue between these people and us involved inquiry into «what is the means of happiness?» and they wanted to say «the virtues» (which would actually be true), it would be unnecessary to take any other step than to agree with them about this, without more ado. But since, as I say, the issue is not «what is the means of happiness?» but «what is happiness and what is the ultimate goal of our nature?», I say both now and always, shouting out loudly to all Greeks and non-Greeks, that pleasure is the end of the best mode of life, while the virtues, which are inopportunely messed about by these people (being transferred from the place of the means to that of the end), are in no way an end, but the means to the end. Let us therefore now state that this is true, making it our starting-point.”

Given that Pleasure is the goal, we must therefore ask if "meaning" or "meaningfulness" is a feeling of pleasure in itself, or instrumental to obtaining pleasure.

In answering that question we should ask: "How many possible types of feelings are there within which "meaning" might be included?"

Epicurus holds that there are only two "feelings" in life - pleasure and pain - and at all times that we are conscious of feeling anything, we are feeling one or the other.

Diogenes Laertius X-34 : ”The internal sensations they say are two, pleasure and pain, which occur to every living creature, and the one is akin to nature and the other alien: by means of these two choice and avoidance are determined.“

Epicurus PD03 : ”The limit of quantity in pleasures is the removal of all that is painful. Wherever pleasure is present, as long as it is there, there is neither pain of body, nor of mind, nor of both at once .“

Cicero - On Ends Book One, 30 : ”Moreover, seeing that if you deprive a man of his senses there is nothing left to him, it is inevitable that nature herself should be the arbiter of what is in accord with or opposed to nature. Now what facts does she grasp or with what facts is her decision to seek or avoid any particular thing concerned, unless the facts of pleasure and pain?

Cicero - On Ends Book One, 38 : Therefore Epicurus refused to allow that there is any middle term between pain and pleasure; what was thought by some to be a middle term, the absence of all pain, was not only itself pleasure, but the highest pleasure possible. Surely any one who is conscious of his own condition must needs be either in a state of pleasure or in a state of pain. Epicurus thinks that the highest degree of pleasure is defined by the removal of all pain, so that pleasure may afterwards exhibit diversities and differences but is incapable of increase or extension.“

The first appearance of the phrase 'meaning of life' in the written record of the English language dates only from 1831:

SARTOR RESARTUS: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdrockh, by Thomas Carlyle, ~1831 CHAPTER IX. THE EVERLASTING YEA.

"Temptations in the Wilderness!" exclaims Teufelsdrockh, "Have we not all to be tried with such? Not so easily can the old Adam, lodged in us by birth, be dispossessed. Our Life is compassed round with Necessity; yet is the meaning of Life itself no other than Freedom, than Voluntary Force: thus have we a warfare; in the beginning, especially, a hard-fought battle. For the God-given mandate, Work thou in Well-doing, lies mysteriously written, in Promethean Prophetic Characters, in our hearts; and leaves us no rest, night or day, till it be deciphered and obeyed; till it burn forth, in our conduct, a visible, acted Gospel of Freedom. And as the clay-given mandate, Eat thou and be filled, at the same time persuasively proclaims itself through every nerve,—must not there be a confusion, a contest, before the better Influence can become the upper?

"To me nothing seems more natural than that the Son of Man, when such God-given mandate first prophetically stirs within him, and the Clay must now be vanquished or vanquish,—should be carried of the spirit into grim Solitudes, and there fronting the Tempter do grimmest battle with him; defiantly setting him at naught till he yield and fly. Name it as we choose: with or without visible Devil, whether in the natural Desert of rocks and sands, or in the populous moral Desert of selfishness and baseness,—to such Temptation are we all called. Unhappy if we are not! Unhappy if we are but Half-men, in whom that divine handwriting has never blazed forth, all-subduing, in true sun-splendor; but quivers dubiously amid meaner lights: or smoulders, in dull pain, in darkness, under earthly vapors!—Our Wilderness is the wide World in an Atheistic Century; our Forty Days are long years of suffering and fasting: nevertheless, to these also comes an end. Yes, to me also was given, if not Victory, yet the consciousness of Battle, and the resolve to persevere therein while life or faculty is left. To me also, entangled in the enchanted forests, demon-peopled, doleful of sight and of sound, it was given, after weariest wanderings, to work out my way into the higher sunlit slopes—of that Mountain which has no summit, or whose summit is in Heaven only!" … On the roaring billows of Time, thou art not engulfed, but borne aloft into the azure of Eternity. Love not Pleasure; love God. This is the EVERLASTING YEA, wherein all contradiction is solved: wherein whoso walks and works, it is well with him."

Note that this text is considered a parody of Hegel, and that modern scholars find Carlyle's own opinions difficult to isolate. Here is a quote from Carlyle himself in a letter:

Finally assure yourself I am neither Pagan nor Turk, nor circumcised Jew, but an unfortunate Christian individual resident at Chelsea in this year of Grace; neither Pantheist nor Pottheist1, nor any Theist or ist whatsoever; having the most decided contem[pt] for all manner of System-builders and Sectfounders—as far as contempt may be com[patible] with so mild a nature; feeling well beforehand (taught by long experience) that all such are and even must be wrong. By God's blessing, one has got two eyes to look with; also a mind capable of knowing, of believing: that is all the creed I will at this time insist on.

1'Pot-theist'; Carlyle was accused of pan-theism. Pot, pan, you get the idea

Accordingly, we don't have record of Epicurus directly using the term "meaning" in regard to pleasure, but we do know from the surviving texts that Epicurus categorized every feeling in life which is not painful as pleasurable. Is "meaning" something that is pleasurable or painful? Most of us would likely agree that "meaningfulness" or "meaning" is something that generates a positive emotion and that is the reason that many people suggest we should seek it. Given that all positive emotions are categorized by Epicurus as a part of pleasure, Epicurus would then say "Yes," - meaning or meaningfulness is a desirable goal because it is pleasurable.